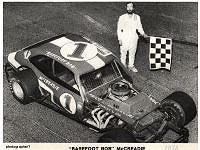

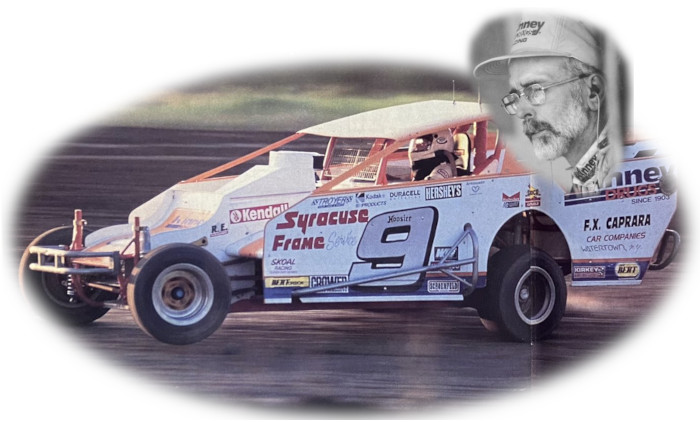

Robert D. "Barefoot" McCreadie

Watertown, NY

19.Jan.1951 - 15.May.2024

King of the hill: The long road to glory for DIRT racing's 'Barefoot Bob' McCreadie

by Sean Kirst, columnist for The Post-Standard. Published: Aug. 20, 1993

Twenty-five years ago, long before Bob McCreadie became the Arnold Palmer of dirt-track racing, he took a job in Watertown shoveling blacktop. McCreadie was a teenager, newly released from a court-ordered year at the Berkshire Industrial Farm in Canaan, where he was supposed to forget how to hot-wire an ignition. He was ready for a new kind of influence, and he noticed how his boss, Ronny Granger, pitched in with the crew and got hot tar on his hands. McCreadie didn't miss the point. A few weeks ago, Granger was hired for a pretty good job - paving the looping driveway at a sprawling house high atop a Watertown hill. To McCreadie, it brought a perfect close to the circle.

"I'm real proud of where I came from," said the guy the promoters call "Barefoot Bob," and that sensibility comes through loud and clear to the fans. To the people who operate the DIRT racing circuit, McCreadie represents "crossover" - the celebrity link between a specialized sport and a more mainstream audience. McCreadie, 42, is not the classic figure you would pick for the role. He is skinny, whiskered, basically blind in one eye. He says that is never a problem. "I can't say I focus on any one thing," he said. "You need to be almost abstract in your vision."

Even by McCreadie's standards, this has been a magic summer. He has won 23 DIRT feature races, giving him a shot at the DIRT record of 34, set by Danny Johnson in 1989. The swarm of appreciative fans gets bigger each week in the pits of Canandaigua or Weedsport or Rolling Wheels in Elbridge, feeding what is already fevered devotion. A line of specialty Matchbox miniatures, designed like McCreadie's famous No. 9 car, quickly sold out. Last year, a McCreadie promotion at a Watertown drug store drew a crowd estimated at 4,000. He is the undisputed favorite in a sport that attracts hundreds of thousands of spectators each summer. "A lot of the other guys are just too stuck up," said Michael Champlain, a fan from Bath who waited in line to shake McCreadie's hand after a recent race at Canandaigua.

To Frederick Fitch, owner of Syracuse Frame Service and a No.9 sponsor, the defining "Barefoot Bob" episode was at Rolling Wheels in 1990. A 5-year-old with leukemia, offered the chance for anything at all, asked the Make-A-Wish Foundation if he could have a car just like No.9. McCreadie loved the idea. "A wonderful human being," said Kathy Grossman, who coordinated that wish. "Bob and his people couldn't have done more for this child." The No. 9 crew made the boy an identical, scale-model go-cart. They scrounged around and came up with a kid-sized helmet. And McCreadie startled everyone at the track by handing the child his championship trophy from the 1986 Miller 200 at Syracuse, the most coveted of all DIRT racing awards. In the only possible conclusion, "Barefoot Bob" went out that night and won the race. The place choked up, then went crazy. "It was like God was there," Fitch said.

McCreadie sees it all as his duties as ambassador. "Sometimes you're tired, especially if you didn't win, and you just don't feel like talking to people, " McCreadie said. But he knows they come from the same place as him, and they ask for only a nod of recognition. So McCreadie stays put until he's talked to all comers, an approach that is absent from most other pro sports. You understand why that happens when you visit the place where he grew up.

Beginnings

The shop that houses the famous No. 9 is built next to the duplex where McCreadie was raised, in a gritty Watertown neighborhood of chipped paint and faded bungalows. As a child, McCreadie recalls, his family "had nothing." Bob's wife of 19 years, Sandy, grew up nearby. Two years ago, the McCreadies moved from the old neighborhood into a house in the country, overlooking the city. To McCreadie, who could reside happily in a garage with an engine, the house was a way to say thanks to his family. Still, Sandy and Bob had to persuade Bob's reluctant mother, Betty, to vacate the old duplex that housed most of her memories. McCreadie loves the new place, the view and the solitude, the deer that wander without fear in his yard. But he can put up with only so much tranquility. Early each morning, he dresses quietly and drives downhill, to his shop. The house, he knows, is good for his kids. Even in the frantic minutes before a race, when he smokes his last cigarette and the crew scrambles to get the car ready to go, he often stops to sign autographs for children by the fence. "I can relax with kids," he said. "I think they like me because I'm no different than they are."The hardest place

To appreciate McCreadie, you have to see a DIRT race, the way the modifieds tear up the straightaways at speeds sometimes climbing toward 150 mph, then skid into smoky turns where the "features" are won or lost. McCreadie claims he is no athlete, only a technician, but at that speed it takes an athlete to survive. McCreadie has rarely been injured. His worst moment came in Weedsport five years ago when he broke his back in a freak accident. It left his mother so frightened that she will no longer go to the track to watch him race. The accident did not particularly scare her son. The only time he's spooked, he maintains, is when he's a passenger on the street in someone else's car, and the driver tries to impress him by going real fast. "They think they have to show off," he said. He remembers the weeks following his injury as the lowest of his life. McCreadie is restless, frenetic, and he was forced to spend hours sitting on his can, until he finally tossed out everything the doctors said. He started to jog, and he started to heal. It was time for McCreadie to get back to his shop. "The rush of being around cars," he said, "is almost like an addiction." McCreadie said winning a race is no better than making a new find in the shop, where 10 or 11 people come and go, all of them hooked to the rhythm of one engine. There is a sense of triumph, he said, in abruptly realizing how some minor adjustment can make a profound difference. This year, McCreadie's crew discovered they were "basically overpowering the back of the car." It was a big deal, a change from years of one specific approach. They made the adjustments, and McCreadie's performance went up another notch. He credits his crew with that kind of discovery, and they throw the credit back at him. "Bob has always wanted to win," said Hugh Naylor, a Canadian whose day job is counseling people with head injuries and whose specialty at night is maintaining the tires. "The way he drives, he never gives up, and that's why we work so hard for him."'A wild kid'

McCreadie was not born into racing. His dad was a taxi driver and his mom was a cook, and neither really cared about cars. McCreadie was a slender child who underwent surgery to straighten out his crossed eyes, although he never gained any vision in his left eye beyond blurry outlines. While he claims he had no natural feel for motors, his mother remembers it differently. When McCreadie was still in grade school, his parents bought a wrecked car for him to tinker with. It was trash, a pile of parts. One day McCreadie called for his mom. She went outside to find he had the thing started. Those skills, before long, got him in trouble. McCreadie ran with some boys whose specialty was hot-wiring and stealing cars, and that "hobby" persuaded a judge to ship McCreadie to Berkshire. "I was a wild kid," he said. Yet Berkshire had a shop where he could mess around with engines, and McCreadie absorbed a bigger lesson about human nature. "It helped me learn to get along with everyone, " he said. "It was interracial, and there were a lot of street kids out of New York City." Years later, it explained why he knew better than to flee his neighborhood as it became racially diverse. He returned to Watertown, but endured only one or two more years of school. He already knew what he wanted to do. He got into some demolition derbies - neglecting, at first, to inform his disapproving parents. His earliest races were often on the straightaways of Interstate 81. Before long, he was getting embarrassed in his early tries at Watertown Raceway. Things came together in the late 1970s, when Glenn Donnelly assembled the coalition of tracks that became known as the DIRT circuit, and McCreadie - the embodiment of the everyman - emerged as a true personality. He was labeled "Barefoot Bob" for a one-time decision to handle a cramped gas pedal by driving without shoes. "He's done for us what Richard Petty did for NASCAR, " said Gary Spaid, a DIRT statistician. "His popularity really helped it take off." McCreadie said he has no interest in the national racing scene. He would need to move south, and he does not want to uproot his family. And while a Kinney Drugs sponsorship has ended most of his financing problems, McCreadie isn't sure he'd find the cash to handle full-blown stock-car racing. Besides, the guy already makes a good living. He won't disclose his annual winnings, but his triumph at Syracuse in 1986 - the Indy equivalent for DIRT circuit racers - paid enough that he could finally build his own shop. For the past couple of years, he has even done some winter racing in Australia. To McCreadie, the real prize is being able to work exclusively at the thing he loves most, on the same city block where he spent his whole life - a combination that rarely happens in a transient United States. Maybe his working-class fans see in that success what they wish for themselves, a regular guy who can make it on his own terms."There's a real rush," McCreadie said, "in starting out last and finishing first." That is what he remembers each night, as he shuts down his car by the house on the hill.

- Bob McCreadie links

- 1987 Super Dirt Week program (all pages with story of Bob's 1986 win)

- please links, stories, stats or images so we can all remember Bob McCreadie.

- -

- stats

- -

return to tribute index page

[JakesSite Home] [Supers1] [Supers2] [Mods-other] [Tomsuper] [Super Stats]